Fiona Ehlers

May 31, 2019, Der Spiegel

“Keep down your voice, lower your eyes”

Princess Latifa planned her escape from her father’s palace in Dubai for seven years – and failed. Every year, hundreds of women leave the Gulf States to escape their husbands and fathers.

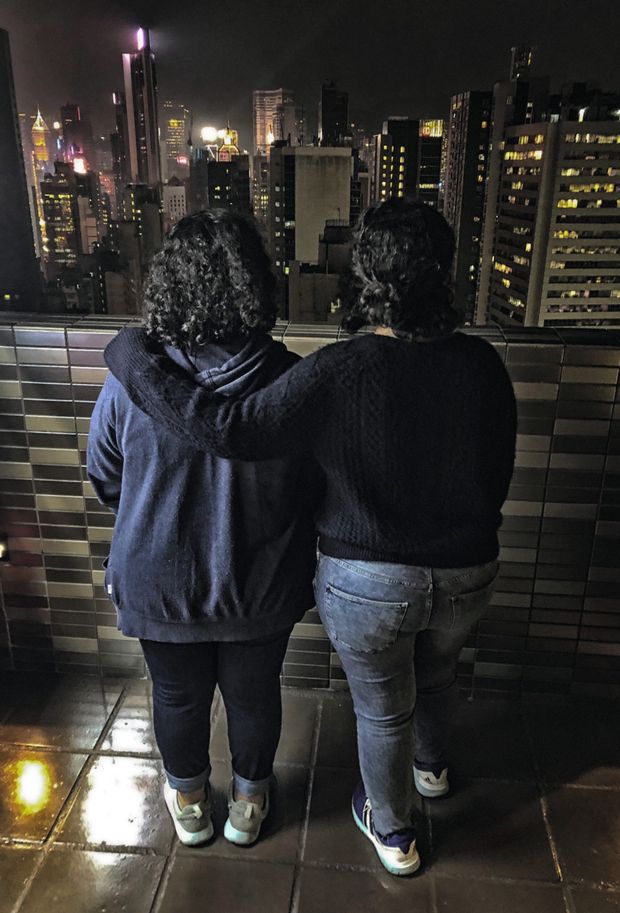

The two sisters from Saudi Arabia eagerly pick up on what they encounter in the streets of Hong Kong: men in pinstripes, women in breezy dresses on the ferries in Kowloon Bay, night markets, cocktail bars, entertainment districts. The young women enjoy their new freedom, you can see that. They walk around town in ripped jeans and with uncovered hair on a day in March; they have many questions. Best of all, they say, people here like the way they live, what they love, all of which is so exciting.

Then they get into an elevator and sit down at the window of a hotel room high above Hong Kong, the exact location must remain secret, the cell phones are switched off, photos only from behind. As with whistleblowers, these two sisters from Saudi Arabia, 18 and 20 years old, use the names Rawan and Reem, but in reality they’re different.

The sisters tell the story of their escape, cautiously, haltingly, because on this March day they are still afraid that their father could track them down and bring them home by force. Only sometimes they have to laugh out loud. When the younger one, Rawan, curses. Or when Reem recounts how as little girls they toasted with their juice glasses, as they had seen in banned films. And their mother ran out of the room, screaming “haram”, “forbidden.”

Reem and Rawan are two of at least a thousand women who flee Saudi Arabia each year because they can no longer endure the patriarchy and oppression from husbands and fathers – they are called “runaway girls” in their homeland, “runaways.” Rawan doesn’t like the term. She thinks it sounds like they’re rebelling, “we risk our lives,” she says. Rawan and Reem were stranded in Hong Kong while fleeing to Australia last September.

Arab “runaways” have been around since the 1970s, but never before have they been as visible as they are today. They team up with activists who organize legal assistance and accommodations. They put videos on YouTube – like Rahaf al-Qunun, 18, whose escape to Bangkok and eventually Canada caused an international stir in January, or Dina Ali Lasloum, who was dragged back to Riyadh by relatives in Manila in 2017.

The ruling families in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are putting pressure on women with their media. The “Saudi Gazette” blames the phenomenon of “hostile states”, which seduced the women to defame Saudi Arabia. “Our enemies are trying to infiltrate our society with this cancer.”

Reem and Rawan grew up in a middle-class family. Their father, they recount in conversation in Hong Kong, works in Riyadh’s prison administration. As far back as they can remember, they were guarded by two older brothers and a younger one. “They kept us like slaves,” Reem says. Two words could define their childhood: shame and prohibition.

“There was no joy in our house,” complains Rawan, “the worst was when we laughed out loud.” The worst brother was the youngest, ten years old, Reem says. He constantly ordered: “Keep your voice low, look down, cover your skin.” Even at home they had to cover themselves, and beatings were normal. Their future husbands were destined to be their cousins, the sisters did not have a choice. What allowed them to survive their youth? “That they were able to comfort each other,” says Reem.

For two years, the women planned their escape, put money aside, a few thousand dollars, and discussed everything again and again. In September, during a family vacation in Sri Lanka, they finally seized the opportunity: they stole their passports from their parents’ hotel room and secretly booked plane tickets to Australia via smartphone. They draped their prayer robes on the bed so it looked like they were asleep. Then they made their way to the airport.

More than five hours later, in the transit zone of the Hong Kong airport, their plans began to falter: two men were waiting at the gate to take their passports and boarding passes from them. When the men turned out to be employees of the Saudi Arabian Consulate, the sisters knew they had been betrayed.

They only had minutes to act now. In the bathroom, Rawan, the younger one, made a decision. She snatched the passports from the men’s hands and ran out of the transit zone with her sister into the crowd outside passport control, then on to the Airport Express to Hong Kong Central, into the middle of a strange life. From a hotel, they placed a call for help on Twitter. A Frenchman read the tweet, contacted a lawyer and local aides on the ground. More than a dozen times, the girls had to change their accommodation before being allowed to travel on to a third country in March.

Those who speak with them understand that these are not spoiled teenagers, as is often insinuated in their homeland, but smart, courageous women full of fighting spirit and confidence.

Role model for Reem and Rawan and many other “runaways” is Princess Latifa, 33, daughter of the Emir of Dubai and premier of the United Arab Emirates. The video, released after her failed escape and seen on YouTube by more than two million people, ends with the words, “If I do not succeed, then I hope at least that something changes for the better.” (SPIEGEL 50/2018)

Latifa was aware of the danger that her disobedience posed. She must have guessed what damage her disappearance would mean to her father, the Emir. The video was shot by her, just before she fled, in the Dubai apartment of Tiina Jauhiainen, her Finnish fitness trainer, one of the few who was privy to the princess’ plans.

Jauhiainen, 42 years old, sits in a London cafe on a spring afternoon. She still remembers very clearly how she met Latifa in Dubai in 2010. Jauhiainen was asked to go to an estate on the outskirts of the city. She was supposed to give training lessons to a wealthy Emirati in Capoeira, the Brazilian fighting dance.

It was only gradually that Jauhiainen realized who this Emirati woman was, who lived in a 40-room palace with exercise rooms, pool and 100 employees. Latifa, as her former trainer recounts, lived a bleak existence despite all her riches. She was not allowed to leave Dubai, she was not allowed to study. For seven years, Latifa had planned her escape, with the help of a French-American former secret agent, Hervé Jaubert.

In February 2018, the women managed to escape to Oman – and from there to a yacht of the ex-agent. Latifa wanted to ask for political asylum in Miami. But the yacht was hijacked by the Indian Coast Guard. “On the eighth day (at sea) we heard gunshots on deck at about 10pm,” says Jauhiainen. Drowsy, she climbed up to the deck – and saw red laser dots of guns on her body. “Shoot me right here,” Latifa pleaded, “just don’t take me back to Dubai!”

The attackers ignored the request. Latifa and Jauhiainen were brought back to Dubai. Jauhiainen was in solitary confinement, interrogated, and scared to death. After two weeks, she was eventually deported to Europe by the authorities. Since then, she has been on the run, changing her place of residence on a regular basis – and fighting with lawyers for the release of her friend Latifa, with whom she has not been able to speak for more than a year.

Someone sent her a photo a few months ago. It shows the former Irish President Mary Robinson, a friend of the Emirati ruling family, next to a sedated looking Princess Latifa at a dining table. In London at the café, Jauhiainen looks at the photo: “See Latifa’s face, rigid as a mask, her gaze, completely clouded, as if we were falling for this production.”

Women like Latifa, Reem, and Rawan have countless reasons to flee the Persian Gulf countries; the most important is guardianship law. It applies in some Middle Eastern countries, but hardly anywhere is it practiced as strictly as in Saudi Arabia and the Emirates. Under the law, women are not allowed to leave the country without permission from the guardian (i.e., the father, husband or brother), some can not even leave the house, nor are they allowed to study.

Saudi Arabia’s crown prince Mohammed bin Salman portrays himself as a reformer. He has relaxed the dress code and lifted the ban on driving for women. Women like Reem and Rawan do not much appreciate these innovations, “what do reforms bring us when mother thinks they are the devil’s stuff and father says, ‘you will never drive a car, I forbid that!’”, they ask.

Women fleeing from countries like Saudi Arabia often rely on a community of escape helpers, internet activists and human rights activists in the U.S., Europe, and Australia. In the Gulf states, they can do nothing, but at the borders, the transit zones of the airports, and later in exile, they are there already.

Jérémy Desvages, 32, a programmer from France, is one of them. He read the tweet that Reem and Rawan had sent from the Hong Kong hotel, and from then on offered help, as did 15 other refugees from the Gulf. He provides emotional assistance, solicited lawyers and shelters. He visited Reem and Rawan in Hong Kong. Why? “Because I have the opportunity to do so,” he says, showing cries for help and evidence on his mobile: bruises to the upper arms, bruised black-eyes.

Desvages also looked after Hind Albolooki, a Emirati from Dubai, 42 years-old. She has behind her what Reem and Rawan might have expected had they stayed in Saudi Arabia: a marriage that was hell for 22 years. Unlike Princess Latifa, Albolooki is now safe, with her asylum application pending in Germany.

But she pays a high price for her freedom: She left her four children. “What mother does such a thing voluntarily?” she asks, crying bitterly.

Hind Albolooki says she never thought of running away, even when she heard about Princess Latifa. Like all of Dubai, she followed Latifa’s escape, even though the video was blocked after one day.

Albolooki was a spoiled young woman, her mother chose the husband, a medical student from an influential family. Her mother-in-law chose the wedding dress. Albolooki succumbed, gave birth to children, in return she was offered a life of luxury: a villa in Jumeirah, trips to Milan to Gucci and Prada, a blue Maserati Ghibli.

Her husband, a senior employee at the ministry of health, gave her sedatives. He beat her and raped her, according to Albolooki, cheated on her with her sister-in-law and forced her to watch him having sex with other women. “My family knew these stories,” she says. “No one ever said a word.”

Then Albolooki made the mistake of talking about divorce. The marital war began. She had to hand over the car key, her four credit cards, the diamond-studded watch. The Family Council was called. They had tried everything, the men said, Albolooki would not obey, “go and get your passport, we will keep it”.

Albolooki apparently did as she was told. But her daughter had realized the seriousness of the situation, she handed her mother the passport, plus a handbag with cash. A domestic worker let her escape through the garden gate. Albolooki developed a courage she had not suspected: she hid near the house on a construction site, buried her cell phone in the sand so she couldn’t be located, put her Abaja on, and stayed that way for several hours. With the help of a taxi driver and a friend, she got a new mobile phone and a plane ticket to Europe.

She made it to Germany. She will have to make money for the first time in her life, but she feels well prepared and wants to encourage others. Does she regret having left? “Not one day.”